- January 20, 2026

- Admin

- 0

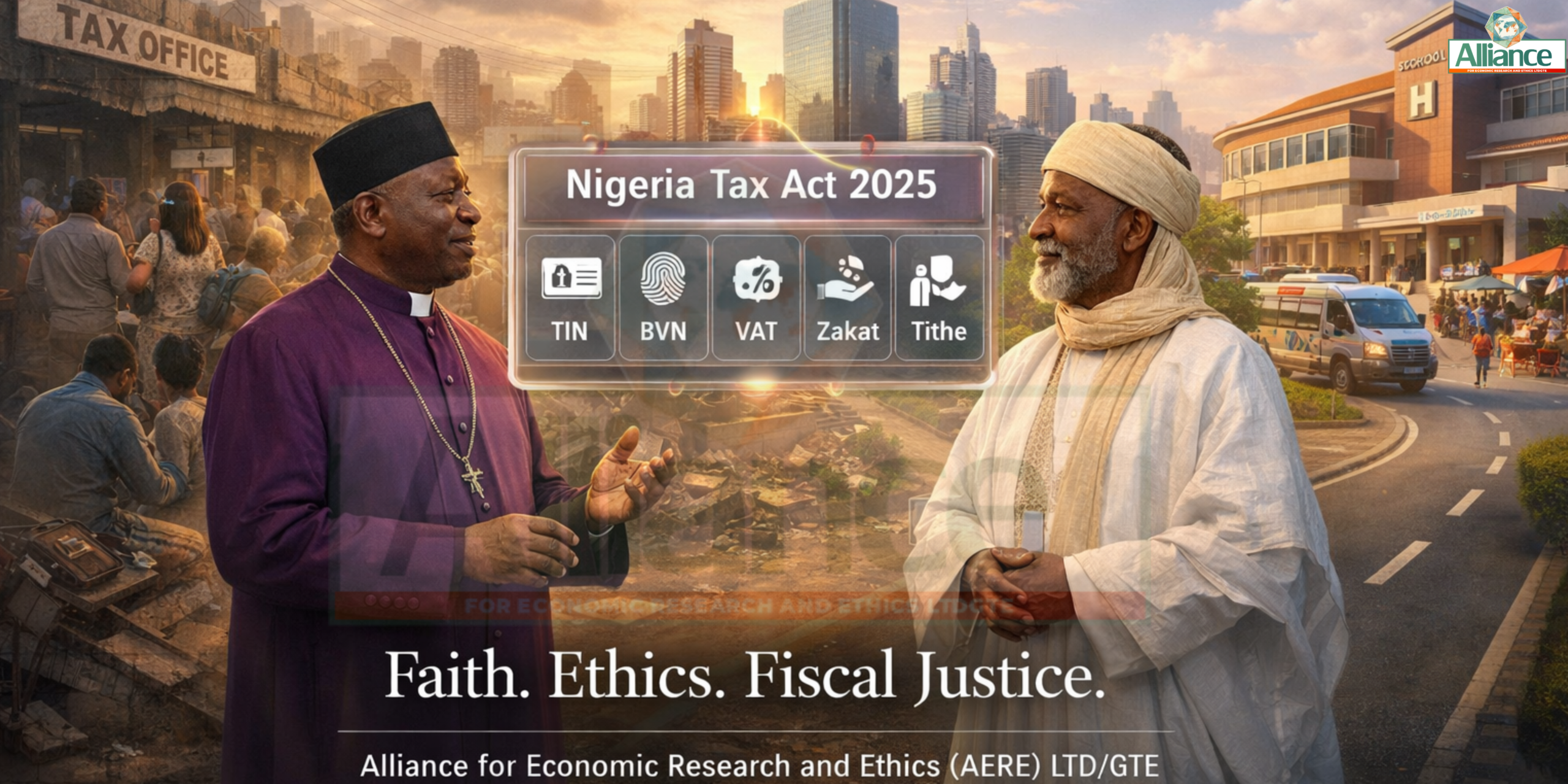

HARMONIZING ZAKAT, WAQF, AND CHRISTIAN STEWARDSHIP UNDER NIGERIA’S 2025 TAX ACT

Abstract

The enactment of the Nigeria Tax Act (NTA) and the Nigeria Tax Administration Act (NTAA) in 2025 represents the most significant overhaul of the nation’s fiscal landscape in decades. This research examines the intersection of these legislative reforms with the religious financial obligations of Nigeria’s two primary faiths: Islam and Christianity. By centralizing revenue collection and tightening the definitions of "charitable activities," the 2025 Tax Act introduces new compliance burdens for religious institutions and their adherents. This article analyzes how Islamic pillars, specifically Zakat (obligatory alms) and Waqf (endowments), as well as Christian practices of tithing and stewardship, navigate this unified tax regime. The study identifies potential friction points, such as the tension between the spiritual requirement for donor anonymity and the state’s demand for transparency via digital identification links. Furthermore, it explores the legal status of religious organizations as "Companies Limited by Guarantee" and the implications of the new VAT self-accounting requirements for non-governmental organizations. Through a synthesis of legal analysis and theological perspectives, the paper proposes a "Faith-State Compact" to mitigate double taxation concerns and ensure that the pursuit of fiscal sustainability does not inadvertently stifle the social safety nets provided by religious bodies. The findings suggest that while the 2025 Tax Act promotes modernization and reduces tax fragmentation, its success in the religious sector depends on the professionalization of institutional financial desks and a collaborative oversight framework between the Nigeria Revenue Service (NRS) and faith-based stakeholders.

- Introduction

There is an old, perhaps apocryphal, tale often told in Nigerian clerical circles about a tax collector and a flamboyant preacher who arrived at the Pearly Gates simultaneously. To the preacher’s astonishment, the tax collector was ushered into a sprawling mansion, while the preacher was given a modest bungalow. When the preacher questioned this divine audit, the gatekeeper replied, "While you preached, people slept; but when he sent out tax assessments, everyone started to pray." This anecdote, while lighthearted, underscores the historical tension and the profound psychological impact of fiscal intervention in the realm of the spiritual. In the Nigerian context, this tension has reached a critical juncture with the introduction of the 2025 Tax Act, a legislative suite designed to harmonize a previously fragmented and often chaotic tax system.

The 2025 Tax Act is not merely a technical adjustment of rates; it is a fundamental reimagining of the social contract between the Nigerian state and its citizens. For decades, religious institutions operated within a gray area of the law, enjoying broad exemptions under the guise of "public character" while occasionally venturing into commercial activities that blurred the lines between sanctuary and shop. The new regime, characterized by the Nigeria Tax Act (NTA) and the Nigeria Tax Administration Act (NTAA), seeks to bring order to this complexity by centralizing collection and mandating a digital paper trail for all financial transactions [1]. For the devout, this raises a pressing question: how does one balance the "Nisab" of Zakat or the "Tenth" of the Tithe with the rigorous demands of the Nigeria Revenue Service (NRS)?

This article delves into the strategic implications of these reforms for Islamic and Christian financial practices. It moves beyond the binary of "God versus Caesar" to explore how faith-based philanthropy can be harmonized with modern tax administration. As the digital economy grows toward an estimated $300 billion by 2025, the government’s drive for revenue mobilization increasingly targets the institutional transparency of all entities, including those previously shielded by religious sentiment [2]. By examining the nuances of Zakat deductibility, the tax status of Waqf assets, and the reporting requirements for church-led charities, this study aims to provide a roadmap for compliance that preserves spiritual integrity while fulfilling civic duty.

- The Great Shift: From the Old Tax Regime to the 2025 Tax Act

The transition to the 2025 tax regime marks the formal end of an era defined by legislative proliferation and administrative duplication. Prior to these reforms, the Nigerian tax system was a labyrinth of multiple taxes, with state and federal authorities often competing for the same revenue pools, leading to significant inefficiencies and a high cost of compliance for businesses and non-profits alike [3].

2.1 Key Legislative Changes and Modernization Efforts The core of the 2025 reform lies in the amalgamation of various tax laws into a unified legislative framework. This consolidation is primarily achieved through the Nigeria Tax Act and the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, which aim to simplify the legal structure and promote fiscal sustainability [4]. One of the most significant shifts is the move toward a data-driven administration system. The new laws emphasize the integration of the Tax Identification Number (TIN) with other national identifiers like the National Identification Number (NIN) and Bank Verification Number (BVN).

This modernization effort is not just about technology; it is about closing the loopholes that allowed for widespread tax evasion. Under the old regime, the lack of coordination between different tax authorities meant that an entity could claim exemptions in one jurisdiction while generating taxable income in another. The 2025 Act introduces a "Cloud Unified Tax Portal," which serves as a centralized hub for filing returns and managing assessments [5]. For religious organizations, this means that the era of "cash-in-the-boot" financial management is effectively over. Every donation, if it is to be used as a basis for tax exemption or deduction, must now be part of a verifiable digital record.

2.2 Shift from Multiple Taxes to Unified Collection One of the primary grievances of the Nigerian taxpayer has been the "multiplicity of taxes," where a single economic activity could be subject to numerous levies from different tiers of government. The 2025 Tax Act addresses this by establishing a single, unified tax collection process [6]. This centralization is intended to reduce the administrative burden on taxpayers and eliminate the predatory practices of "touting" that often characterized local government revenue collection.

The unification of VAT administration is a cornerstone of this shift. The 2025 regime seeks to provide clarity and ensure uniform application of VAT provisions across the federation [id:1768613981032]. For religious bodies that operate schools, hospitals, or printing presses, this change is particularly relevant. Previously, these institutions might have negotiated informal exemptions with local officials. Now, the law requires a standardized approach where the "commercial" arm of a religious organization is clearly decoupled from its "spiritual" arm. The unified collection system ensures that while the sanctuary remains a place of worship, the sanctuary’s bookstore is treated as a taxable retail outlet.

2.3 Impact on Non-Profit and Religious Organizations The 2025 Tax Act significantly tightens the criteria for what constitutes a "charitable" organization. Under the previous Companies Income Tax Act (CITA), the definition of "public character" was broad and often exploited. The new reform clarifies that for an organization to maintain its tax-exempt status, its profits must not be distributed to any individual and must be reinvested solely in the pursuit of its charitable objectives [7].

Furthermore, the 2025 regime introduces a mandatory self-accounting requirement for VAT on taxable supplies received by NGOs, including religious associations [8]. This means that even if a mosque or church is exempt from paying income tax on its donations, it must still account for and remit VAT on the goods and services it consumes or provides in a commercial capacity. The "Prophet-Profit" loophole, where large-scale religious investments were shielded from the national purse, is being systematically closed. The state now views these institutions through the lens of their economic footprint, requiring them to demonstrate their "public benefit" through rigorous documentation rather than mere clerical assertion.

ISLAMIC FAITH

- Zakat and Waqf: Islamic Financial Pillars in the New Tax Landscape

Islamic finance, rooted in the principles of social justice and wealth redistribution, offers a unique set of challenges and opportunities within the 2025 tax framework. The two primary pillars, Zakat and Waqf, are central to the financial life of the Ummah and represent a significant portion of non-state social welfare in Nigeria.

3.1 Tax Deductibility of Zakat: Opportunities and Hurdles Zakat, the obligatory 2.5% alms on qualifying wealth, is a religious duty that many Muslims view as a "divine tax." In the context of the 2025 Tax Act, the debate centers on whether Zakat payments should be recognized as a tax credit or a deductible expense. If the state’s goal is "fairness," then a Muslim paying both Zakat and statutory income tax faces a form of "double taxation" that could be seen as a penalty for religious compliance.

The 2025 Act provides a window for documented religious giving to be treated as a deductible expense, provided the recipient is a registered "Company Limited by Guarantee" or a recognized charitable trust. However, the hurdle remains the "Nisab"—the minimum wealth threshold for Zakat. In some cases, the "Nisab" is lower than the government’s tax-free threshold, meaning the religious law is "stricter" than the state law for the relatively poor. For the wealthy, the challenge is proving the payment. The NRS now requires e-invoicing and digital receipts for any deduction to be valid [5]. This creates a tension with the spiritual preference for "secret giving," where the left hand does not know what the right is doing. To benefit from the 2025 Act’s provisions, Islamic institutions must adopt professional accounting standards that bridge the gap between spiritual anonymity and fiscal transparency [9].

3.2 Waqf Assets: Property Tax and Charitable Exemptions Waqf, or Islamic endowment, involves the permanent dedication of property or assets for charitable purposes. Under the 2025 Tax Act, Waqf assets are positioned as the ultimate tax-exempt trusts, provided they are properly structured. These assets often include land, buildings, and investment portfolios intended to fund hospitals, schools, or poverty alleviation programs [10].

The new tax regime’s focus on property tax and capital gains tax makes the registration of Waqf assets crucial. If a Waqf is not legally registered and recognized by the NRS, the income generated from its properties could be subject to corporate taxation. The 2025 Act encourages the formalization of these endowments. By shifting from informal communal holdings to structured trusts, Islamic institutions can protect these assets from the taxman while serving the public good. The humorous irony here is that while the state wants its share of every "transaction," a well-structured Waqf is essentially a "transaction-free zone" for the benefit of the poor, which aligns perfectly with the 2025 Tax Act’s stated goal of supporting genuine charitable activities.

3.3 Documentation and Reporting Requirements for Islamic Institutions The most profound change for Islamic institutions under the 2025 Tax Administration Act is the shift to proactive reporting. The Act provides a uniform procedure for the administration of tax laws, facilitating a consistent and efficient process [11]. For Islamic NGOs and Zakat committees, this means maintaining detailed records of donors and beneficiaries.

The integration of NIN and BVN into the tax system means that the NRS can now track high-value transfers. This poses a challenge for Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance within the religious sector. Islamic institutions must now ensure that their "Amanah" (trust) includes robust book keeping. Failure to do so does not just risk a divine reprimand; it risks the seizure of assets by the state. The 2025 Act essentially demands that religious leaders become "Faith-Accountants," ensuring that every kobo of Zakat and every acre of Waqf is accounted for in a way that satisfies both the Creator and the Commissioner. This professionalization is a "wake-up call" for the sector to move away from traditional, informal methods toward a transparent, data-driven model of religious philanthropy.

CHRISTIAN FAITH

- The Tithe and the Treasury: Christian Stewardship and Tax Compliance

The Christian community in Nigeria, characterized by its diversity of denominations and its massive economic footprint, faces a parallel set of challenges under the 2025 Tax Act. The practices of tithing and "special offerings" are not only spiritual exercises but also significant financial movements that the state can no longer ignore.

4.1 Legal Status of Tithes, Offerings, and Church-Led Charities Under the 2025 Tax Act, the legal status of tithes and offerings remains largely protected as voluntary personal gifts to religious organizations. However, the "protection" is contingent upon the institutional structure of the church. The NRS increasingly scrutinizes whether these funds are being used for the "public character" activities defined in the new law or are being diverted into private pockets.

For a church to ensure that its tithe-funded projects remain tax-neutral, it must often register its charity arms as separate legal entities, such as Companies Limited by Guarantee [7]. This separation is vital because the 2025 Act is designed to tax the "shop" but not the "sanctuary." When a church operates a multi-billion-naira university or a commercial printing press, the income from these ventures is now clearly taxable. The "Holy Humor" here is that while a "miracle seed" might be sown in a spiritual sense, the NRS expects a "verifiable receipt" if that seed is to be claimed as a tax-deductible expense by a corporate donor. The 2025 regime effectively mandates a "separation of powers" within the church: the spiritual leader handles the souls, while a professional bursar handles the books.

4.2 Distinguishing Personal Giving from Institutional Income A major area of friction under the 2025 Act is the distinction between the personal income of religious leaders and the institutional income of the church. In many Nigerian congregations, the lines between the "Man of God" and the "Ministry of God" are historically blurred. The new tax administration laws, with their emphasis on digital tracking and BVN links, make this ambiguity a significant legal liability.

One of the most significant shifts in the 2025 Tax Act is the aggressive push to close the "Prophet-Profit" loophole. In previous decades, the distinction between the personal wealth of a religious leader and the institutional income of the church was often blurred. The new Act, supported by the integration of National Identification Numbers (NIN) and Bank Verification Numbers (BVN), allows the NRS to monitor high-value transactions with greater precision. Personal gifts to clergy members, often referred to as "honorariums" or "blessings," are now scrutinized under the lens of personal income tax if they constitute a regular stream of revenue.

Data indicates that the centralization of tax collection aims to ensure that "voluntary giving" does not become a conduit for tax evasion. For instance, when a congregant gifts a luxury vehicle to a religious leader, the 2025 Act may view this as a taxable benefit-in-kind unless it is clearly documented as an asset of the religious institution. This requires a professionalization of church accounting desks. The era of "cash-in-the-boot" management is being replaced by the "Faith-Accountant," who must ensure that institutional income is used for the "Ummah" or the "Body of Christ" rather than personal enrichment [15]. This institutionalization is essential for maintaining the integrity of the faith while satisfying the state's demand for fiscal transparency.

4.3 Transparency in Church Social Responsibility (CSR) Programs Many Christian organizations in Nigeria run extensive social responsibility programs, including hospitals, schools, and disaster relief. The 2025 Tax Act provides incentives for these activities, but only if they are transparently documented. The requirement for "demonstrable public benefit" means that churches must now provide data on the number of beneficiaries and the impact of their programs to justify their tax-exempt status.

The 2025 Tax Act recognizes the vital role of Church Social Responsibility (CSR) in national development, but it demands verifiable evidence of impact. Much like the Islamic concept of Waqf, Christian CSR programs—ranging from scholarships to community health centers—are seen as essential partners in achieving Sustainable Development Goals [16]. However, the Act introduces stricter reporting requirements for these programs to qualify for tax deductions or exemptions. It is no longer sufficient for a church to claim it is "helping the poor"; it must provide a breakdown of expenditure and a list of beneficiaries that can be audited.

This transparency requirement serves a dual purpose: it protects the institution from allegations of money laundering and ensures that the tax-exempt status is not abused. Research shows that structured charitable giving, when properly documented, can serve as a significant tax incentive for donors [17]. For Christian organizations, this means adopting reporting standards that mirror the "Zakat-style" specificity, where funds are allocated to particular social needs. By professionalizing CSR, churches can demonstrate their contribution to the national economy while shielding their core religious activities from unnecessary state interference.

- Identifying and Managing Clashes between Faith and State

The intersection of the 2025 Tax Act and religious practice is fraught with potential clashes, primarily centered on the tension between spiritual mandates and secular oversight. Managing these areas of friction requires a delicate balance and a collaborative approach between religious leaders and tax authorities to ensure that civic duty does not infringe upon religious freedom.

5.1 Areas of Friction: Privacy of Giving versus Audit Transparency The most significant area of friction is the conflict between the religious value of anonymous giving and the state’s requirement for audit transparency. In both Islam and Christianity, the highest form of charity is often that which is done in private. However, the 2025 Tax Administration Act’s focus on Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and "Know Your Customer" (KYC) principles requires religious institutions to identify high-value donors [11].

The NRS's use of data-driven collection means that "anonymous" Zakat or Tithes become difficult to sustain when the bank accounts used for transfers are linked to a Tax Identification Number (TIN). This digital oversight is often perceived as an intrusion into the sanctity of the sanctuary. To resolve this, policy guidelines must be developed that allow for "blind trusts" or aggregate reporting, where the total volume of donations is verified without necessarily exposing the identity of every small-scale donor. Nevertheless, for high-net-worth individuals, the 2025 Tax Act makes it clear that the "umbrella of God" is no longer a shield against the "eye of the taxman" [18].

5.2 Double Taxation Concerns: Religious Obligation versus Civic Duty For the devout Nigerian, the combined weight of Zakat/Tithes and the 2025 statutory taxes can feel like an excessive burden. This "double taxation" concern is particularly acute in a struggling economy where the state’s social services are often perceived as inadequate. The 2025 Act’s unified collection system, while efficient, does not inherently account for the 10% or 2.5% already "taxed" by the faith.

A Muslim paying 2.5% Zakat or a Christian paying 10% Tithe (plus offering) already contributes significantly to social welfare. When the state demands an additional percentage in income tax, the question of "double taxation" arises. There is a humorous but poignant observation that the religious "Nisab" (the minimum wealth threshold for Zakat) is sometimes lower than the government’s tax-free threshold, making the religious law "stricter" for the poor than the state law [19].

A proposed solution is the introduction of a "Religious Social Responsibility" (RSR) credit. Under this guideline, documented religious giving to registered charities could be deducted from a taxpayer’s taxable income up to a certain percentage. This would recognize the "civic value" of religious giving, as these funds often go toward education and healthcare—areas where the state is also an actor. Such a policy would harmonize the "Covenant" with the "Code," ensuring that the citizen is not penalized for their faith while the state ensures its revenue targets are met. Without such harmonization, the state risks alienating the religious community, leading to lower compliance rates and a sense of fiscal injustice [17].

5.3 Proposed Policy Guidelines and Collaborative Oversight To harmonize faith and the fiscus, a "Faith-State Compact" is proposed. This would involve the creation of a joint consultative committee comprising the NRS, the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), and the Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs (NSCIA). This committee would oversee the development of specific guidelines for the 2025 Tax Act, ensuring that religious peculiarities are respected. For example, the recognition of Waqf assets as tax-exempt trusts could be formalized, providing a clear legal framework for long-term communal investments [20].

Furthermore, the government should provide technical assistance to religious organizations to help them upgrade their financial reporting systems. Compliance should be framed not as a burden but as a form of "Amanah" (Trust). By demonstrating that tax compliance protects the institution's assets from legal jeopardy and enhances its social impact, the state can promote a culture of voluntary compliance. Collaborative oversight would also ensure that the definition of "charitable activity" remains inclusive, reflecting the diverse ways in which faith-based organizations contribute to the Nigerian society [21].

- Conclusion

The 2025 Tax Act represents a transformative shift in Nigeria’s fiscal landscape, moving from a fragmented and often opaque system to one characterized by centralization, data integration, and accountability. For the religious community, this transition is both a challenge and an opportunity. While the new requirements for transparency and documentation may initially seem like an encroachment on religious autonomy, they also provide a platform for faith-based institutions to formalize their immense contributions to national development.

Harmonizing Zakat, Waqf, and Christian stewardship with the state's fiscal code requires more than just legal compliance; it requires a theological and institutional evolution. Religious organizations must embrace the "Faith-Accountant" model, ensuring that every naira given in the name of God is accounted for with the same rigor expected by the state. Simultaneously, the state must recognize that religious giving is a vital component of the social safety net, deserving of fiscal recognition and support [22].

Ultimately, the goal of both faith and the fiscus should be the same: the welfare of the people and the prosperity of the nation. By resolving the clashes between privacy and transparency, and by addressing the concerns of double taxation through innovative policy guidelines, Nigeria can create a harmonious environment where the "Covenant" and the "Code" work in tandem. In this new era, good bookkeeping is not just a statutory requirement; it is a modern form of worship, ensuring that the resources meant for the poor and the community are managed with the highest level of integrity and "Amanah" [23].

References

- Nigeria’s Tax Reform Acts 2025: Strategic Implications for Business Operations and Recommended Adaptive Strategies. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5438856

- Taxation of Digital Activities and Cross-Border Transactions: An Appraisal of Nigeria’s Strategy Vis-A-Vis Global Perspective. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5020946

- The 2025 Nigerian Tax Reform Acts: Analysis of Key Provisions and Implementation Challenges. ssrn.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5797744

- Legal Appraisal of the 2024 Nigerian Taxation Bills. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5113900

- Enhancing Revenue Mobilization in AfCFTA through Nigeria’s Cloud Unified Tax Portal: Opportunities and Challenges. net. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Beauden-John/publication/396160486_Enhancing_Revenue_Mobilization_in_AfCFTA_through_Nigeria’s_Cloud_Unified_Tax_Portal_Opportunities_and_Challenges/links/68dfc40b02d6215259b8fdef/Enhancing-Revenue-Mobilization-in-AfCFTA-through-Nigerias-Cloud-Unified-Tax-Portal-Opportunities-and-Challenges.pdf

- EVALUATING NIGERIA’S NEW TAX REFORM AND ITS IMPACT ON FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY THROUGH NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT. AUN Journal of Social Sciences. https://journals.aun.edu.ng/index.php/aunjss/article/download/177/123

- A REVIEW OF THE REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS FOR FOREIGN PARTICIPATION IN NIGERIA’S BUSINESS ECOSYSTEM. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5268750

- Tax Treatment of Non-Governmental Organisations Under the Tax Reforms Acts, 2025. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5695422

- Al-Habibiyyah – the just foundation. https://alhabibiyyah.org/

- THE ROLE OF ISLAMIC FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN PROMOTING PHILANTHROPY IN NIGERIA: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF PRACTICES, IMPACT, AND …. KWASU Law Journal. https://journals.kwasu.edu.ng/index.php/kwasulj/article/view/511

- Nigeria Tax Administration Bill, 2025. org.ng. https://ngfrepository.org.ng:8443/handle/123456789/6678

- AN APPRAISAL OF INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR TAXATION OF INCOME OF NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION IN NIGERIA. https://unijerps.org/index.php/unijerps/article/view/907

- International Law Framework for Taxation and the Sustainable Development Goals in Nigeria. Available at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4993714

- The waqf: a global financial instrument. European Journal of Islamic Finance. https://ojs.unito.it/index.php/EJIF/article/view/11161

- Alms tax (zakat) law intricacies: an institutional and governance‐based analysis. Thunderbird International Business Review. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/tie.70053

- The role of Waqf in CSR: models from Indonesia and Malaysia and new proposals. Emerald. 2025. https://www.emerald.com/jiabr/article/doi/10.1108/JIABR-03-2025-0126/1335287

- The Role of Zakat Dedication as a Tax Incentive in Enhancing Compliance and Achieving Financial Justice… Academia. https://www.academia.edu/download/125995475/IJMAE_Volume_12_Issue_6_Pages_899_928.pdf

- Waqf over a century: innovation and tradition in shaping social equity and sustainable development. Emerald. 2024. https://www.emerald.com/ijssp/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/IJSSP-12-2024-0625/1302644

- THE TRANSFORMATION OF ABU YUSUF’S FISCAL PRINCIPLES: FORMULATING INCLUSIVE SHARIA POLICIES FOR ECONOMIC STABILITY AND WELFARE IN …. https://jurnal.staialhidayahbogor.ac.id/index.php/ad/article/view/9009

- Reviving Waqf-Based Endowments for Sustainable Teacher Training in Northern Nigeria. https://ejournal.gomit.id/index.php/ijopate/article/view/404

- Waqf: From classical charitable system to modern financial tool. Emerald. 2024. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ijoes-10-2024-0354/full/html

- Islamic Finance’ S Role In Social Equity And Poverty Alleviation: Trends And Gaps. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Almabrok-Ahmid/publication/398067724_ISLAMIC_FINANCE’S_ROLE_IN_SOCIAL_EQUITY_AND_POVERTY_ALLEVIATION_TRENDS_AND_GAPS/links/694be4e1a1fd0179890b2df3/ISLAMIC-FINANCES-ROLE-IN-SOCIAL-EQUITY-AND-POVERTY-ALLEVIATION-TRENDS-AND-GAPS.pdf

- Analysis of waqf studies: a hybrid review. Emerald. 2024. https://www.emerald.com/ijoes/article/doi/10.1108/IJOES-11-2024-0378/1271097

About The Alliance for Economic Research and Ethics (AREET) LTDGTE: The Alliance for Economic Research and Ethics (AREET) LTDGTE is a Nigerian non-profit working to strengthen both the private and public sectors in Nigeria. It achieves this by conducting independent evidence-based research, advocating for sensible policies, providing regulatory support for businesses, bringing stakeholders together, and promoting transparent ethical reforms to improve Nigeria's "Ease of Doing Business".

Thank you.